The term ‘fake news’ has become popularised over the last few years. The term refers to information that has no basis in fact, but is presented as being factually accurate in a deliberate attempt to spread misinformation for propaganda purposes.

Hunting is often on the receiving end of this approach to ‘news’. It is increasingly evident that this is misleading the public, media and policy makers and leading to uninformed policy decisions.

A recent glaring example of this is the now widespread claim that “only 3% of trophy hunting revenues end up in local communities”. This claim has its roots in a 2013 report¹ (The $200 million question: How much does trophy hunting really contribute to African communities?) commissioned by the African Lion Coalition and prepared by Economists at Large Pty Ltd.

The report states that “Research published by the pro-hunting International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation and the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation […] finds that hunting companies contribute only 3% of their revenue to communities living in hunting areas.” This ‘fact’ has now been taken up and is used widely in both traditional and social media to discredit the validity of hunting as a tool for wildlife conservation and rural development.

As the purported originators of this ‘fact’ we provide clarification. The Economists at Large report quotes a CIC and FAO publication² (The Contribution of Hunting Tourism: How Significant is This to National Economies?) in which the figure of 3% does appear. However, the figure of 3% is only relevant to one country (Tanzania), at a particular moment in time (2008), and is only reflective of a small portion of the benefits that communities can receive from regulated, sustainable hunting.

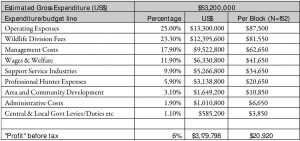

Table 7 (seen below) in the CIC/FAO report shows the figure “3.10%” in a set of data that estimates the expenditure of the hunting industry in Tanzania for the period of 2008, however, 3.10% is only representative of the expenditure on area and community development.

The report categorises “area and community development” as, “Payments to CBO organizations, payments to communities for concession fees, resource fees, payments for welfare and education etc.”

Table 7 from Vernon R. Booth (2010): The Contribution of Hunting Tourism: How Significant is This to National Economies? In Contribution of Wildlife to National Economies. Joint publication of FAO and CIC. Budapest. 72 pp.

As you can see from the table above, the Economists at Large report fails to mention various other expenditures that can support local communities. This includes wages to locals, social welfare taxes, fees going to the Tanzania Wildlife Division, payments to professional hunters, payments to service providers such as hotels, and more.

And once again, we stress that this data is relevant only to Tanzania in 2008.

Taking a country specific figure – one that is not even representative of all the benefits that communities can receive from regulated, sustainable hunting – and generalising it to apply to all hunting in African countries is extremely misleading, bringing into question the competence, credibility and motivations of the report’s authors.

Quantifying the exact extent of benefits generated from hunting – including cash income, employment, protein, reduction of human wildlife conflict, improved social infrastructure (roads, schools, clinics), enhancement of local governance and community empowerment – for communities throughout Africa is not feasible, not least because there are significant variations from country to country. Brief research reveals that in Namibia 100% of income from trophy hunting on communal land goes to the local community: whilst in Zimbabwe, 100% of income from hunting goes to the local Council – 55% of which goes to local communities and the remainder is allocated to wildlife management and local administration. Whilst these figures do not represent an accurate picture of community benefits from hunting in even these countries, they demonstrate that extrapolating from one country to another is a meaningless exercise.

Complicating this situation further is the fact that regulations and laws governing hunting revenues are not always optimum or adhered to. For example, in 2019, rural communities in Zambia took their government to court over withheld trophy hunting funds. Despite legislation requiring the redistribution of funds to rural communities, the Treasury have failed to do so over the past several years. The decision to take legal action should not be taken as a criticism of trophy hunting as a management tool; instead, it comes out of an expectation of fair governance, meaning that local communities receive their fair share of profits.

Conservation in Africa takes place in a complex and evolving context of competing environmental, social, political and economic concerns. Understanding the role and implications of hunting within this context requires rigorous research based on sound science. It is incumbent on those reporting on hunting, conservation and community development to inform themselves appropriately and avoid regurgitating ‘fake’ news. To do less is to disregard those peoples whose livelihoods depend on wildlife, as well as best conservation practice.

[1] Economists at Large, 2013. The $200 million question: How much does trophy hunting really contribute to African communities? A report for the African Lion Coalition, prepared by Economists at Large, Melbourne, Australia.

[2] Vernon R. Booth (2010): The Contribution of Hunting Tourism: How Significant is This to National Economies? In Contribution of Wildlife to National Economies. Joint publication of FAO and CIC. Budapest. 72 pp.